Italian poets have crafted some truly beautiful literature over the centuries. Some of them even nabbed the Nobel Prize for Literature, proving that their verses not only wowed their homeland but also made a lasting impact on the global stage. No surprise there, considering the gorgeous musicality of the Italian language, one that can inspire and make words flow effortlessly.

Reading these Italian poems today is like opening a time capsule. It’s not just about discovering some linguistic gems; you’re getting a sneak peek into Italy’s past as well as delve into the captivating lives of the artists who penned these verses.

In this guide, are 7 classic Italian poems that every learner of Italian should know. I’ve also included English translations, a summary of each poem plus useful grammar and vocabulary notes. These bonus notes will help you understand the poem’s meaning as well as shed light on its grammatical structure that will help improve your Italian.

Cominciamo! (Let’s begin!)

By the way, did you know you can learn Italian anytime, and anywhere? Yep, it’s true! Go here to find out how you can learn Italian more efficiently using my unique 80/20 method.

1. San Martino by Giosuè Carducci

Giosuè Carducci – R. Borghi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“San Martino” (Saint Martin’s Day) is one of the first poems taught to Italian children in elementary school. It’s so popular that it was even transformed into a catchy song by the Italian entertainer Fiorello.

The poem was penned by Giosuè Carducci, the very first Italian to snag the prestigious Nobel Prize in Literature in 1906. In this piece, he vividly captures the season of autumn, mixing melancholic tones with lively celebrations in a village on St. Martin’s Day, a special occasion celebrated on November 11th that marks the end of the harvest season.

| Italian | English Translation |

|---|---|

| La nebbia agli irti colli piovigginando sale, e sotto il maestrale urla e biancheggia il mar;

ma per le vie del borgo dal ribollir de’ tini va l’aspro odor dei vini l’anime a rallegrar.

Gira su’ ceppi accesi lo spiedo scoppiettando: sta il cacciator fischiando su l’uscio a rimirar

tra le rossastre nubi stormi d’uccelli neri, com’esuli pensieri, nel vespero migrar. | The fog to the bare hills soars in the thin rain, and below the wind howls and churns the sea;

yet through the hamlet’s alleys from the fermenting casks goes the pungent scent of wines to touch a soul with glee.

On the firewood, turns the skewer crackling: stands the hunter whistling, on the threshold to see

in the reddening clouds flocks of black birds, like exiled thoughts as in the dusk they flee. |

Poem Summary

It’s sunset in a quaint village in Maremma, right in the heart of Tuscany (the poet’s birthplace). As locals get ready to party, you can smell the delicious combo of wine and juicy meat on the grill. Meanwhile, fog starts rolling in over the hills, and the foamy waves of the sea crash against the rocky shores in the cool mistral wind. In the middle of all this, there’s this enigmatic hunter observing birds soaring through the sky, as if he’s contemplating thoughts drifting in the air.

Italian Grammar Notes and Useful Vocabulary to Know

The poem’s structure is pretty simple when it comes to grammar. One interesting thing to notice is how Carducci switches between verb tenses, using the present (“sale” – soars; “gira” – turns), gerund (“scoppiettando” – crackling; “fischiando” – whistling), and infinitive (“rimirar” – to see; “migrar” – to flee) to create a sense of time standing still.

He uses descriptive words that might sound a bit old-fashioned but truly paint a vivid picture:

- irti colli (rugged hills with little vegetation)

- biancheggia (meaning “whitens,” like when the foam of the waves makes the sea look white)

- ribollir (from “ribollire,” meaning to ferment)

- ceppi (wooden logs)

- stormi (flocks)

- vespero (the evening)

2. L’Infinito by Giacomo Leopardi

“L’Infinito” (The Infinite) is one of the most cherished poems in Italian literature, part of a collection of brief nature poems known as Idylls. Leopardi wrote it at the tender age of 21, and as you read it, you’ll likely be amazed by the fact that this young man was already such a creative genius.

“L’Infinito” (The Infinite) is one of the most cherished poems in Italian literature, part of a collection of brief nature poems known as Idylls. Leopardi wrote it at the tender age of 21, and as you read it, you’ll likely be amazed by the fact that this young man was already such a creative genius.

Beyond its literary appeal, this poem holds a universal relatability. It not only speaks to everyone but also provides insights into the poet’s personal struggles. Leopardi sought solace in contemplating “the infinite” during a challenging period in his life. Faced with difficulties, he attempted to break free from Recanati, his hometown in Le Marche. Additionally, he battled with eye troubles that plunged him into despair.

| Italian | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Sempre caro mi fu quest’ermo colle, E questa siepe, che da tanta parte Dell’ultimo orizzonte il guardo esclude. Ma sedendo e mirando, interminati Spazi di là da quella, e sovrumani Silenzi, e profondissima quiete Io nel pensier mi fingo; ove per poco Il cor non si spaura. E come il vento Odo stormir tra queste piante, io quello Infinito silenzio a questa voce Vo comparando: e mi sovvien l’eterno, E le morte stagioni, e la presente E viva, e il suon di lei. Così tra questa Immensità s’annega il pensier mio: E il naufragar m’è dolce in questo mare. | Always dear to me was this still hill, And this hedge, which in so many ways Of the last horizon the look excludes. But sitting and aiming, endless Spaces beyond that, and superhuman Silences, and deepest quiet I pretend in thinking; where for a while The heart is not afraid. And like the wind I hear rustling among these plants, I that Infinite silence to this voice I am comparing: and the eternal comes to my mind, And the dead seasons, and the present And alive, and the sound of her. So between this Immensity drowns my thought: And shipwreck is sweet to me in this sea. |

Poem Summary

While the exact mountain isn’t specified in the poem, after some analysis we know that Leopardi stands atop Mount Tabor, near his home in Recanati, as he contemplates the scenery. As he looks out, there’s an irritating hedge in the way, making him use his imagination. All of a sudden, he starts picturing a vast open space and a silence so deep it’s hard for people to grasp. Initially, this feeling of infiniteness – a key theme in the poem – makes him a little dizzy. However, soon it turns into a comfortable mental escape where he can completely immerse himself in his thoughts.

Italian Grammar Notes and Useful Vocabulary to Know

What immediately catches the attention is how Leopardi uses specific groups of words:

Nature: he describes elements of the natural world like

- l’ermo colle (the lonely hill)

- la siepe (the hedge)

- il vento (the wind)

- le piante ( the plants)

- le stagioni (the seasons)

- il mare (the sea)

Senses: the poem is rich in sensory experiences, with terms like

- il guardo (the gaze)

- mirando (looking)

- silenzi (silences)

- quiete (quiet)

- odo (I hear)

- voce (voice)

- il suon di lei (the sound of her)

Space: this is the central theme, with terms like

- interminati spazi (endless spaces)

- infinito (infinite)

- eterno (eternal)

- immensità (immensity)

- ultimo orizzonte (last horizon)

In particular, there’s a deliberate play between distante space (“laggiù” – over there) and nearby space (“qui” – here).

Speaking of space, Leopardi uses many demonstrative adjectives and pronouns (“questo” – this, “quello” – that, etc.) to guide the reader from the world of limited things to the vastness of undefined spaces.

Throughout the poem, he also frequently uses the gerund tense (like “sedendo” – sitting, “mirando” – looking, “v’ comparando” – wanting to compare). This indefinite tense helps convey the idea of the infinite, making the reader feel like they’re in a moment that stretches beyond normal limits.

3. Ho sceso dandoti il braccio by Eugenio Montale

Eugenio Montale – Kaj Hagman., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Eugenio Montale, a major Italian poet from the 1900s and winner of the Nobel Prize for literature in 1975 , wrote one of the sweetest Italian love poems out there: “Ho sceso dandoti il braccio” (I went down arm in arm with you).

In this poem, Montale pours his heart out about his late wife, Drusilla, who was his North Star. When she passed away, Montale found himself stuck in the confusing maze of life for what seemed like forever. She wasn’t his only muse, she was the one who made him feel all the warmth of a family.

His lines really nail that deep feeling of being lost when someone important passes away. You may want to keep a box of tissues handy for this one.

| Italian | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Ho sceso, dandoti il braccio, almeno un milione di scale e ora che non ci sei è il vuoto ad ogni gradino. Anche così è stato breve il nostro lungo viaggio. Il mio dura tuttora, né più mi occorrono le coincidenze, le prenotazioni, le trappole, gli scorni di chi crede che la realtà sia quella che si vede. Ho sceso milioni di scale dandoti il braccio non già perché con quattr’occhi forse si vede di più. Con te le ho scese perché sapevo che di noi due le sole vere pupille, sebbene tanto offuscate, erano le tue. | I went down a million stairs, at least, arm in arm with you. And now that you are not here, I feel emptiness at each step. Our long journey was brief, though. Mine still lasts, but I don’t need any more connections, reservations, traps, humiliation of those who think reality is what we are used to see. I went down millions of stairs, at least, arm in arm with you, and not because with four eyes we see better that with two. With you I went downstairs because I knew, among the two of us, the only real eyes, although very blurred, belonged to you. |

Poem Summary

Montale is lost in his memories, reminiscing about the moments he spent with his wife. While he guided her physically, supporting her every step because of her visual impairment, she became his spiritual compass, the only one capable of accompanying him through the difficulties of life. Walking down the stairs becomes a metaphor for facing life together – a journey described with great realism and heartfelt simplicity.

Italian Grammar Notes and Useful Vocabulary to Know

In this poem, Montale keeps it simple, using everyday language that makes it easy for the reader (and Italian learners) to understand, especially compared to other poems. One interesting word to highlight is “scorni,” an old term for “senso di umiliazione/vergogna” (feeling ashamed or humiliated).

From a grammatical standpoint, there’s a good example of Italian indirect object pronouns in “mi occorrono” (which means “occorrono a me” – I need them). Also, “ho sceso” might sound a bit odd grammatically because usually, “scendere” requires the verb “essere” in compound tenses. However, in cases like this one, “scendere” can be transitive, meaning it can have a direct object (like the stairs in this case) and therefore uses the verb “avere” in compound tenses. Learn more about all 15 Italian tenses here.

4. S’i fossi foco by Cecco Angiolieri

Cecco Angiolieri is a famous Italian poet who made history in 13th-century Tuscany as a master of comic-realist poetry. While Dante Alighieri was deeply immersed in the sophisticated Stilnovo movement, taking a more refined path, Angiolieri opted for an authentic and humorous approach. His writings, filled with cleverness, explored themes like love, local events, and even his own family.

One of Angiolieri’s standout works is the sonnet “S’i fossi foco” (If I were fire), where the poet vents his frustrations about the world around him. Interestingly, even centuries later, his words still strike a chord – the renowned singer Fabrizio De Andrè even turned them into a song in the 1960s!

| Italian | English Translation |

|---|---|

| S’i’ fosse foco, ardere’ il mondo; s’i’ fosse vento, lo tempestarei; s’i’ fosse acqua, i’ l’ annegherei; s’i’ fosse Dio, mandereil’ en profondo; s’i’ fosse papa, allor serei giocondo, ché tutti cristïani embrigarei; s’i’ fosse ’imperator, sa’ che farei? a tutti taglierei lo capo a tondo. S’i’ fosse morte, andarei da mio padre; s’i’ fosse vita, fuggirei da lui; similmente faría da mi’ madre. S’ i’ fosse Cecco com’ i’ sono e fui, torrei le donne giovani e leggiadre, le vecchie e laide lasserei altrui. | If I were fire, I would set the world aflame; If I were wind, I would storm it; If I were water, I would drown it; If I were God, I would send it to the abyss. If I were Pope, then I would be happy, For I would swindle all the Christians; If I were Emperor, do you know what I would do? I would chop off heads all around. If I were death, I would go to my father; If I were life, I would flee from him; The same would I do with my mother. If I were Cecco, as I am and I was, I would take all the women who are young and lovely And leave all the old and ugly for others. |

Translated by David Novak

Poem Summary

In this sonnet, Cecco passionately expresses his dissatisfaction with the world. At first, he wishes he could be like a force of nature or even God and wipe out humanity. Then, he criticizes the top figures of his time – the Pope and the Emperor – and then shifts focus to his parents, who held him back from living a carefree life. Despite the rebellious tone, Cecco later shows a more relatable side, saying that he is simply Cecco and loves beautiful women.

While today we might take voicing our opinions for granted, in the 13th century this was rather daring, considering the fact that being exiled was a potential consequence of going against those in power! Yikes!

Italian Grammar Notes and Useful Vocabulary to Know

The irony of not being able to be all the things he wants to be to get back at the world is expressed through the use of hypothetical sentences, especially those of the second type, which denote the possibility that something may or may not happen and follow the construction: Se + imperfect subjunctive + present conditional. Learn more about this and all other Italian tenses here.

For example: S’i’ fosse foco, ardere’ il mondo (If I were fire, I’d burn the world).

Taking a look at the vocabulary used, the sonnet is packed with old-fashioned words and spellings that aren’t used in Italian today, for example:

- foco (for “fuoco” – fire)

- serei (for “sarei” – I’d be)

- giocondo (“felice” – happy)

- andarei (for “andrei” – I’d go)

- faría (for “farei” – I’d do)

- laide (for “ripugnante” – very ugly)

- lasserei (for “lascerei” – I’d leave)

5. Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare by Dante Alighieri

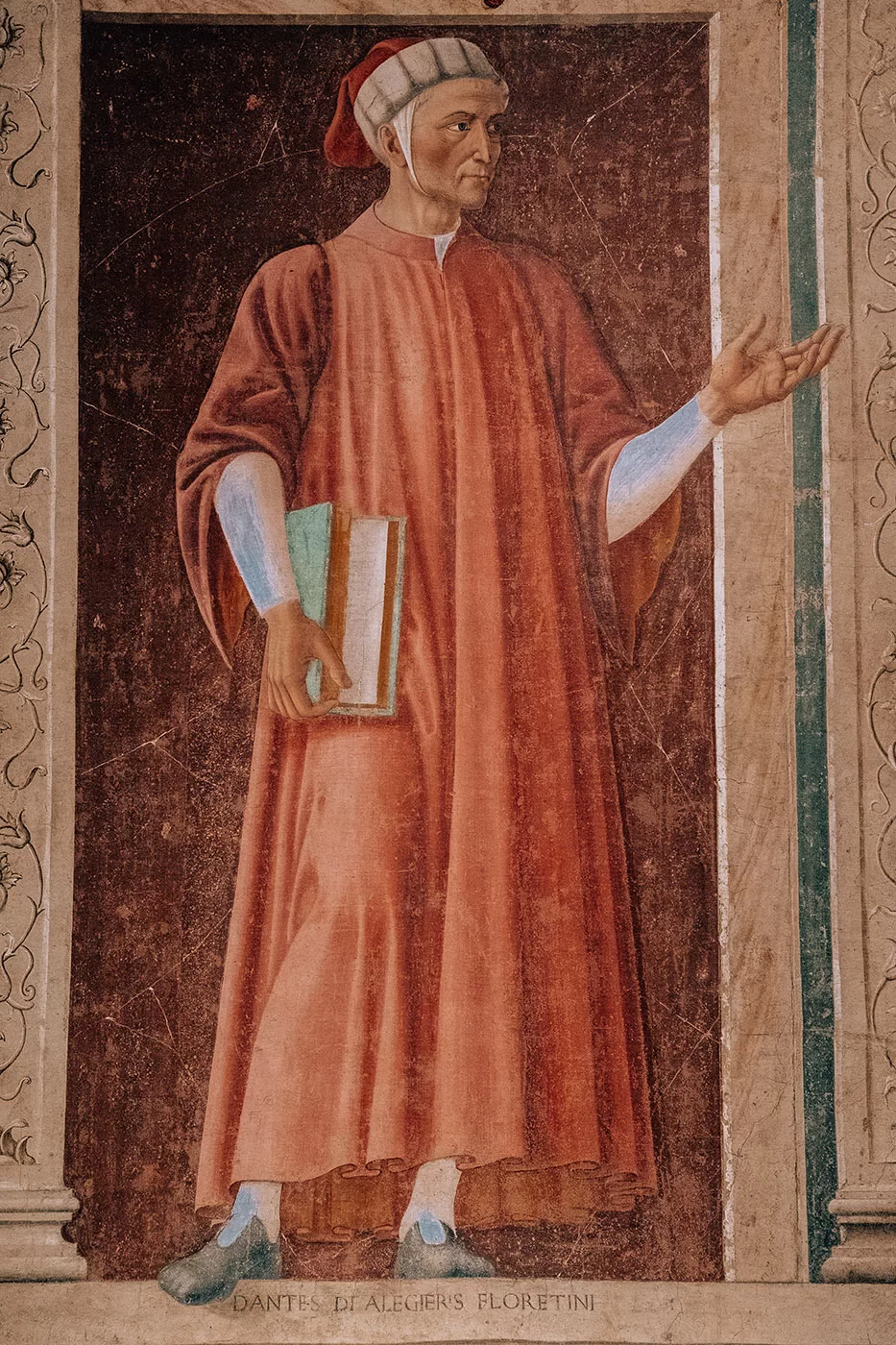

Dante Alighieri at Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

Since I mentioned Dante Alighieri earlier , I have to share one of his most famous poems, “Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare” (So gentle and so dignified appears). It’s a love poem about Beatrice Portinari, a girl he was madly in love with since the tender age of nine. Spoiler: the two hardly even talked!

This poem is from his first-ever published work, the “Vita Nova” (New Life), a mix of prose and poetry all about Beatrice – both as a real-life person and a symbol of deep spiritual love. Dante was definitely taking infatuation to a whole new level!

| Italian | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare la donna mia quand’ella altrui saluta, ch’ogne lingua devèn tremando muta, e li occhi no l’ardiscon di guardare.

Ella si va, sentendosi laudare, benignamente d’umiltà vestuta; e par che sia una cosa venuta da cielo in terra a miracol mostrare.

Mostrasi sì piacente a chi la mira, che dà per li occhi una dolcezza al core che ‘ntender no la può chi no la prova:

e par che de la sua labbia si mova un spirito soave pien d’amore, che va dicendo a l’anima: Sospira. | So gentle and so dignified appears my lady when she greets others, that every trembling tongue becomes dumb, and their eyes do not dare look upon her.

She walks on, hearing herself praised, benignly clothed in humility; and seems to be something arrived from Heaven as a miracle on Earth.

She appears so pleasant tothose who look upon her, and through her eyes a sweetness touches the heart, which cannot be understood by those who feel it not:

and it seems that from her lips emanates a delicate spirit full of love, that speaks to the soul: Sigh |

Poem Summary

In this poem, Dante describes the impact that Beatrice’s greeting has on those fortunate enough to meet her. As she enters a room, everyone goes quiet and can’t even look at her because, well, she has that effect! But it’s not just about her looks, – Dante goes on to tell us that she’s like something heavenly. Her eyes enchant hearts, infusing a magical essence that’s hard to describe if you haven’t witnessed it firsthand. Her enchantment deepens as Beatrice evokes a feeling of love that makes everyone around her sigh in amazement.

Italian Grammar Notes and Useful Vocabulary to Know

This poem was written in the 13th century, so it’s not surprising that some of the words used are a bit outdated. Here are some examples:

- The verb “pare” from “parere,” meaning “to seem.” When Dante says “Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare,” he’s expressing how she seems both gentle and honest. Interestingly, Italians still use “parere” in everyday Italian, like when they say “mi pare brutto rifiutare,” meaning “it seems wrong to refuse.

- The verb “mira“ comes from “mirare,” which translates to “to look.” When Dante uses it, he’s likely describing the act of looking or gazing.

- “Core“ is for “cuore,” meaning “heart.” So, when Dante mentions the “core,” he’s talking about the heart, likely referring to emotions or feelings. People in some parts of southern Italy still use “core” in sayings like “I figli so’ piezz ‘e core,” which means “our children are pieces of our heart” in the Neapolitan dialect.

- “‘Ntender“ means “intendere” (to understand). For instance, in “una dolcezza al core che ‘ntender no la può,” Dante is saying there’s a sweetness in the heart that cannot be understood.

- “Labbia“ stands for “labbra,” which means “lips.”

There are also a couple of interesting examples showing how the relative Italian pronoun “che” is used to link sentences by referencing a noun. For example:

- “una dolcezza al core che ‘ntender no la può” – here “che“ refers to “una dolcezza al core” (the sweetness in the heart).

- “un spirito soave pien d’amore, che va dicendo a l’anima“ – here “che“ refers to “uno spirito soave pieno d’amore” (to a gentle spirit full of love).

6. Lavandare by Giovanni Pascoli

Giovanni Pascoli – Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Giovanni Pascoli is another pivotal figure in Italian poetry during the late 1800s. Central to his philosophy is the belief that within each of us resides a child we tend to forget or ignore as we grow up. It’s the ability to reconnect with this inner child and unveil a distinct perspective on the world that defines a true poet.

Pascoli’s poetry explores themes like nature, grief, family, and rural life. He keeps his writing simple, using vivid imagery to convey thought provoking ideas. A great example of this can be found in “Lavandare” (The Washerwomen), where he subtly explores solitude and abandonment.

| Italian | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Nel campo mezzo grigio e mezzo nero resta un aratro senza buoi che pare dimenticato, tra il vapor leggero. E cadenzato dalla gora viene lo sciabordare delle lavandare con tonfi spessi e lunghe cantilene: Il vento soffia e nevica la frasca, e tu non torni ancora al tuo paese! quando partisti, come son rimasta! come l’aratro in mezzo alla maggese. | In the field half gray and half black A plow stays without oxes, that seems Forgotten, in the light vapour. And the rhythmic washing of the laudresses Comes from the milcourse With its thick splashes and long singsongs. The wind blows and the frond snows under, And you still don’t return to your town! When you left, how I stayed! As the plow, in the middle of the fallow. |

Translated by P.G.Mazzarello

Poem Summary

The poem takes place in a field that’s only half plowed and covered in a soft fog. In the midst of this setting, an old plow left alone grabs his attention. Meanwhile, nearby, he can hear the sweet tunes of washerwomen singing in a nearby mill pond. Their song unfolds a tale of a woman longing for her special someone to come back, feeling sad and melancholic, just like the abandoned plow.

This seemingly simple scene has a profound emotional impact, effectively making us feel the sense of loneliness and abandonment. This mirrors Pascoli’s own inner struggles, as his poetry was profoundly shaped by the deep loss he went through – losing his parents, a sister, and two brothers.

Italian Grammar Notes and Useful Vocabulary to Know

Linked to the idea of a poet being an artist who can connect with their inner child, Pascoli’s way with words is all about infusing rhythm and musicality into his poetry. In “Lavandare,” we can see this through some of the words that imitate sounds, such as “sciabordare” (to shake – think of the lively sound of water) and “tonfi” (thud – here, similar to the sound of splashes).

There’s also this interesting word “frasca,” which is a sort of twig with leaves. In the poem, they fall to the ground like snowflakes. What’s interesting is, “frasca” is used in Italian sayings, like “saltare di palo in frasca,” meaning jumping from one topic to another.

7. A Zacinto by Ugo Foscolo

Ugo Foscolo – François-Xavier Fabre, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ugo Foscolo, who wrote “A Zacinto” (To Zakynthos), is one of the most celebrated Italian poets and who played a pivotal role in the transition from Neoclassicism to Romanticism. In his work, he explored profound themes like love, exile, and the fleeting nature of life, reflecting his deep connection to the tumultuous times of Napoleonic Italy.

Born on the Greek island of Zakynthos, Foscolo moved to Italy early in life, but his connection to his birthplace remained strong. Italy was his home, no doubt, but Zakynthos always held a special spot in his heart.This sentiment shines through in this beautiful sonnet where he expresses the profound longing he experienced for the island.

| Italian | English Translation |

|---|---|

| Né più mai toccherò le sacre sponde ove il mio corpo fanciulletto giacque, Zacinto mia, che te specchi nell’onde del greco mar da cui vergine nacque Venere, e fea quelle isole feconde col suo primo sorriso, onde non tacque le tue limpide nubi e le tue fronde l’inclito verso di colui che l’acque cantò fatali, ed il diverso esiglio per cui bello di fama e di sventura baciò la sua petrosa Itaca Ulisse. Tu non altro che il canto avrai del figlio, o materna mia terra; a noi prescrisse il fato illacrimata sepoltura. | I’ll never step ashore and feel your beach the way I felt it as a barefoot child, or see you waver in the windy reach of goddess-bearing sea. You were the island Venus made with her first smile, Zakynthos, the moment she was born. No song embraced your leafy sky, not even his who sang the fatal storm and how Ulysses, his misfortunes past and beautiful with fame, sailed home at last. Some will not return: I too offend the powers that be, am banned from home. Oh maternal land, my words are all I have to send to you. |

Translated by Leonard Cottrell

Poem Summary

Zakynthos isn’t just a place on the map; it’s a mix of real-life magic and fantasy, beauty and classic charm, tinged with a touch of poetic sadness. It’s the poet’s birthplace, yet it also emanates a captivating mythical aura. As the legend goes, Venus herself was born in the same sea that hugs the island. Together with the perfect weather and lush greenery, it’s practically paradise. Adding a touch of ancient Greece to the mix, the island is surrounded by the same sea that Ulysses sailed through. But while Ulysses eventually made it back to Ithaca, Foscolo can’t shake the feeling that he won’t find his way back to Zakynthos.

Italian Grammar Notes and Useful Vocabulary to Know

The first 11 verses flow continuously without any breaks. Foscolo uses a series of relative clauses (for instance, “colui che l’acque cantò fatali” – his who sang the fatal storm) which give the text a cohesive and uninterrupted feel. The opening line hits hard with a triple negation – “ne più mai” (never). In simple terms, Foscolo is expressing that he will never return to Zakynthos, marking it as a definitive and permanent separation from the place.

The choice of verb tenses is also interesting. Foscolo uses the past tense to talk about childhood (“ove il mio corpo fanciulletto giacque” – the way I felt it as a barefoot child), myth (“mar da cui vergine nacque Venere” – of goddess-bearing sea), and poetry (“colui che l’acque cantò fatali” – his who sang the fatal storm).

On the other hand, the future tense is used to convey the realization of an eternal exile from the island (“Né più mai toccherò”– I’ll never step ashore and feel; “Tu non altro che il canto avrai del figlio” – My words are all I have to send to you).

Lastly, Foscolo adds some Latin words that probably sounded outdated even for his time, like “inclito,” a rather lyrical way of saying that something is extremely famous. He’s also not afraid to play around with spelling, like using “esiglio” instead of the correct “esilio” (exile). It’s like Foscolo wants it to sound harsh, cutting ties and leaving the island behind.

Are you a beginner or an intermediate Italian learner? Got a trip coming up or want to communicate with your Italian partner or relatives in Italian? Learn Italian with my unique 80/20 method

Are you a beginner or an intermediate Italian learner? Got a trip coming up or want to communicate with your Italian partner or relatives in Italian? Learn Italian with my unique 80/20 method

Registrations are now open to join Intrepid Italian, my new series of online video courses that use my unique 80/20 method. You’ll go from a shy, confused beginner to a proficient and confident intermediate speaker, with me as your trusty guide.

You’ll finally be able to connect with your Italian partner, speak to your relatives and enjoy authentic travel experiences in Italy that you’ve always dreamed of, and so much more.

As a native English speaker who learned Italian as an adult, I know what it’s like to feel hopeless and lack the confidence to speak. I know what it’s like to start from scratch and to even go back to absolute basics and learn what a verb is!

Intrepid Italian was created with YOU in mind. I use my working knowledge of the English language to help you get into the ‘Italian mindset’ so you can avoid the common pitfalls and errors English speakers make – because I made them once too! I break everything down in such a way that it ‘clicks’ and just makes sense.

No matter what your level is, there is an Intrepid Italian course for you, including:

- 🇮🇹 Intrepid Italian for Beginners (A1)

- 🇮🇹 Intrepid Italian for Advanced Beginners (A2)

- 🇮🇹 Intrepid Italian for Intermediates (B1)

You can join 1, 2, or all 3 courses, it’s entirely up to you. The best part is that you have lifetime access so you learn anytime, anywhere and on any device.

As your guide, I walk you through each lesson, step-by-step, using my unique 80/20 method. My approach is different from traditional methods because I teach you the most important 20% of the language right from the beginning so you can start to speak straight away.

Each course includes video lessons, audio exercises, downloadable worksheets, bonus guides, a private support community, and lifetime access all designed to streamline your learning while having fun.

It even comes with my famous “Celebrate with a Spritz Guarantee”. After 30 days of using Intrepid Italian, if you don’t want to celebrate your new-found Italian skills with an Aperol Spritz, you don’t have to pay a penny! Cheers! 🥂

Join Intrepid Italian here and start learning today! Ci vediamo lì! (See you there!)

Learning Italian? Check out these Italian language guides

- Italian for Beginners | How to Learn Italian in 3 Simple Steps

- TOP 100 Most Common Italian Words (Plus PDF Cheat-Sheet & Quiz)

- Italian Prepositions:The Only Guide You’ll Ever Need (PLUS Chart)

- 17 Weird Italian Superstitions Italians ACTUALLY Live By

- 17 Must-Know Italian Hand Gestures: The Ultimate Guide

- 10 Ways Natives REALLY Say ‘You’re Welcome’ in Italian

- How to say ‘Please’ in Italian in 9 Ways Like a Native

- 41 Italian Greetings: How to Say ‘Hello’ in Italian Like a Local

- 125 Most Common Italian Phrases for Travel You’ll Ever Need [PLUS Printable]

- 8 DEADLY mistakes in Italian (& How to Avoid Them)

- How to Conjugate Italian Verbs in 3 Simple Steps [Italian for Beginners]

- Is Italian Hard to Learn? 7 Common Mistakes & How to Avoid Them

- Master Days of the Week in Italian (7 Simple Memory Hacks)

- Italian Numbers: How to Count in Italian From 0 to 1 Billion (Plus PDF Download)

- How to Order Food & Drinks in Italian [Italian for Beginners]

- 15 Italian Words You Should NEVER Mispronounce [& How Not To]

- 11 Effective Hacks That’ll Help You Learn Italian So Much Faster

- Top 14 Italian Words You Should NEVER Say [& What to Use Instead]

- 20 Hilarious Everyday Italian Expressions You Should Use

- Romanesco: 25 Cool Roman Dialect Words You Should Use in Rome

- 10 Reasons Why Learning Italian Will Change Your Life

- 10 Italian Expressions Italians Love Saying

- 10 Italian Phrases That Will Instantly Make You Sound more Italian

- Funny Italian Sayings: 26 Food-Related Insults You Won’t Forget

- 15 Romantic Italian Films That’ll Make You Love Italy Even More

- How to Master Common Italian Phrases for Travel (Like a Local!)

Like it? Pin it for later!

Over to you!

Did you enjoy this lesson? Do you have a question? Let me know using the comments section below or join me on social media @intrepidguide or @intrepiditalian to start a conversation.

Thanks for reading and I hope you enjoyed this post.

Like what you see? Subscribe using the form below to have all of my posts delivered directly to your email.